The slogan “Make America Great Again” confuses me. There is so much to unpack in that four word statement. It is a wide open proclamation that seems simple but in reality is so subjective it creates more questions than it can possibly answer, starting with what is great. Can “Great” even be defined and then agreed upon.

MAGA as a slogan is a historical phenomena based on the Rashomon effect. The term Rashomon effect comes from Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 film Rashomon. The movie, according to psychologenie.com, “highlights the contradictory interpretations of the same event by different people. But because these are accompanied by facts, each of these interpretations seem completely plausible … wherein lies the confusion and dilemma.”

What makes MAGA so confusing is whose interpretation of what era of American history we agree upon is or was great. Our history is comprised not of one event but a series of events that lead up to a major event–like say, the Civil War to Reconstruction.

Understanding and interpreting history comes from three sources. The University of California, Berkley’s Department of History says that Primary Sources are “The ‘raw materials’ (or the) foundation of historical research and writing.” It is observations from sources who witnessed history as it was unfolding. Sources like newspaper articles, journals, government documents and the arts all give us information from the past.

Secondary sources are the historiography produced from primary sources. It is the books and articles “that (are) anchored in primary sources and informed secondary sources.” It is the “arguments and interpretations about the past” that emerge from the “foundations of historical evidence (i.e., primary sources).” It is a process of either challenging or supplementing “prevailing interpretations that other historians have made.”

And finally, Tertiary Sources are “Books and articles based exclusively on secondary sources – i.e., on the research of others.” Basically we are dealing with numerous interpretations (sources) and outcomes depending on the combination and permutations of historical events. Like this blog.

The (Rashomon) effect of the subjectivity of perception on recollection, by which observers of an event are able to produce substantially different but equally plausible accounts of it.–Wikitionary

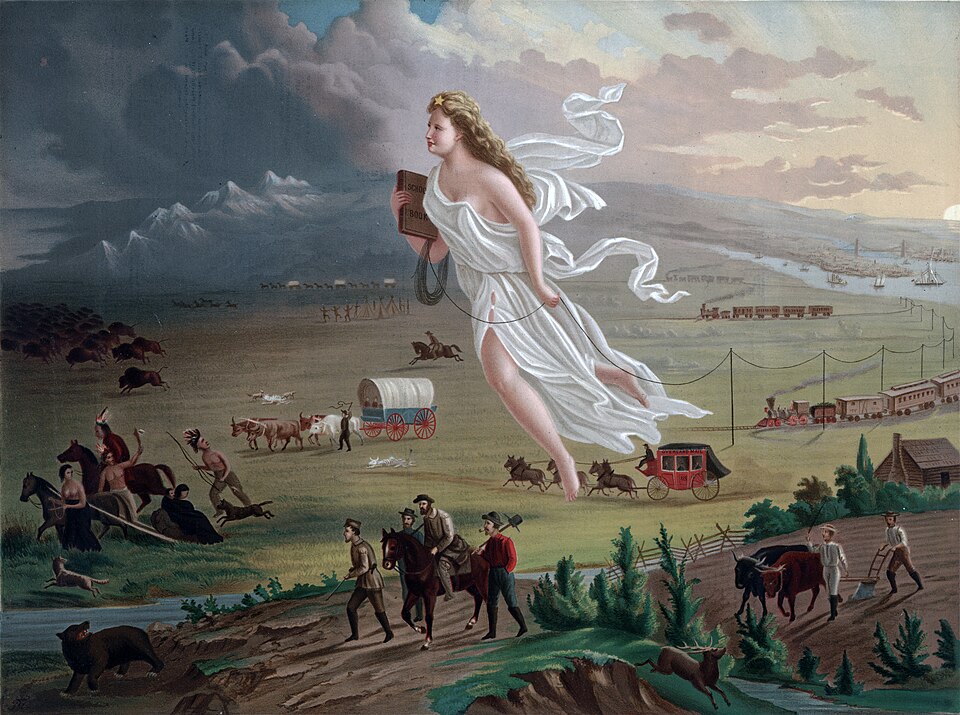

A lot of philosophical beliefs about government and influential individuals in our history can be hashed about as causes for “making America great” starting with the Revolutionary War all the way to someone like Henry Ford and the assembly line. It could be argued that the Louisiana Purchase was an accelerant spurring a population pinned in-between the Appalachians and the Atlantic to move west into what would be a mission of Manifest Destiny, from sea to shining sea with amber waves of grain in-between. It was going west to get to the East–the Orient, and even possibly into Central America. But first Native Americans and Mexico had to be shoved out of the way.

After the War of 1812 a spirit of nationalism took hold. For the next two decades Americans began to take their beliefs west. According to William Earl Weeks, “Manifest Destiny consistently reflected three key themes: the special virtues of the American people and their institutions; their mission to redeem and remake the world in the image of America; and the American destiny under God to accomplish this sublime task.” It was a belief in the virtues of a liberty, justice, and the republican form of government. It encompassed the two “Cs”: Christianity and Capitalism, two concept developed during Colonial times that were now ready to move beyond the Appalachian Mountains–on steroids.

The westward movement in some ways was a religious crusade spawned by the Second Great Awakening. It created a religious incentive to drive west. Indeed, many settlers believed that God himself blessed the growth of the American nation. Afterall the Native Americans were considered heathens and always subject to be converted. By Christianizing the tribes, American missionaries believed they could save souls. Unlike Mountain Men and fur trappers who preceded the missionaries, Manifest Destiny was a fulfillment of God’s will to Christianize the heathen Native American tribes.

It appeared to be America’s sacred duty to expand across the North American continent, to reign supreme in the Western Hemisphere, and to serve as an example of the future to people everywhere. This was Manifest Destiny of the American people.–Building the Continental Empire Americas Expansion from the Revolution by William Earl Weeks

Manifest destiny touched not only on religion; it was an economic and trade crusade; it was about race and patriotism. According to Weeks, “Senator Edward Hannegan of Indiana typified (the) view when in late February 1847 he proclaimed to Congress that ‘Mexico and the United States are peopled by two distinct and utterly nonhomogeneous races. In no reasonable period could we amalgamate.'” A country that depended on slave labor to generate a national income probably did not have a deep seated problem in viewing the western inhabitants, non-Anglo Saxons, Catholics as inferior. The needs of the American expansion to the Pacific generally did not include them. These religious, economic and racial differences would end up in a war with Mexico over Texas. Mexico would lose just about all of the Southwest to include California right up to the border of the Oregon Territory as a result of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). If this could be looked as a ledger sheet, America’s great gain was Mexico’s great loss.

The Oregon Territory was a bit different then battling non Anglo Saxon Catholics and savages. Fighting over the territory was not really an option. Territorial disputes with the former Mother Country over northern and western borders was nothing new. Handling the British bulldog was different then kicking around the Mexican Chihuahua. Britain, unlike Mexico with Texas, could see that American settlers were soon going to populate the Oregon Territory. Both countries had a vested interest in not disrupting the trade between the two countries. And besides, the United States had just engaged Mexico in one war and did not need to fight the British along the northern border at the same time.

Ironing out the Columbia River was done diplomatically. Concessions were made on both sides in modifying the belligerent cry of “Fifty-four Forty or Fight” land grab. This American claim included most of the land west of Continental Divide (current British Columbia) and as far north as the Russian territory of Alaska. Cooler diplomatic heads prevailed setting the border between British North America, Canada a country that we invade twice and at present seem to want to annex, along the 49th parallel instead of the 54th.

Then there was the desire of southerners to find more lands suitable for cotton cultivation. The anti-slavery movement in Northern states was beginning to take off. There was a deep concerned about adding any more slave states to the Union. All of this new land could alter the delicate balance of power of the federal government. Adding states to the Union at this time consisted of bringing in one slave and one free state at the same time. And no president until Abraham Lincoln would consider curbing the growth of our “peculiar institution” to just the South. Settling the boundaries of slavery in these new lands would take two compromises, The Compromise of 1820 (the Missouri Compromise) and The Compromise of 1850. Both were replaced with the idea of popular sovereignty in the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The idea was that the settlers of new territories would decide. Eventually the country decided on war.

And then there was trade, particularly with China. According to The Office of the Historian, “American trade with China began as early as 1784, relying on North American exports such as furs, sandalwood, and ginseng, but American interest in Chinese products soon outstripped the Chinese appetite for these American exports.” (It seems we have always run a trade imbalance with China.) Sixty years later the United States would sign The Treaty of Wangxia that would open up five treaty ports to US trade.

The big problem in tapping into the Far East trade was the United States did not have a suitable port on the West Coast. San Diego, Los Angeles and San Francisco were all in Mexico. That would change after the Mexican-American War. Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Mexico cede 55 percent of its country to the US. America received California, Nevada, Utah along with most of Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. It also settled the long standing feud over the southern border of Texas as the Rio Grande.

It could be argued that Manifest Destiny was a great moment in American history. A lot of the greatness however, was taking place East of the Mississippi. Internal improvements like canals were built to move produce and trade along the many rivers flowing to the Hudson and Mississippi Rivers, and the Great Lakes. Steamships began regular runs up and down the Mississippi and its tributaries. In 1826 in New Jersey John Stevens demonstrated the possibilities of steam locomotion. By the 1830s railroads like the Baltimore & Ohio (B & O) were surveying and laying track. Some Forty years later the railroads connected the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. These were innovations that would be needed to settle and develop the West.

From a certain perspective Manifest Destiny was a time when it could be argued that America being made great. Not so much for Mexico and Native Americans. Therefore greatness may very well depend on the subjective perspective taken in determining what is great as to who benefits by greatness and the stories they tell. To the contrary, there is a good possibility that someone has been disposed, denied or defeated by just standing in the way of making something great.