1851-52 by Bingham, George Caleb (1811-79); Washington University, St. Louis, USA;

After the 1890’s census the Superintendent of the Census declared the frontier closed. This did not mean that Americans could not travel into the West because as we have learned in our history classes it was America’s Manifest Destiny to control all the land between the Atlantic and Pacific. Basically, what the Census Bureau was saying is there was no real frontier line like the Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi River or the Rocky Mountains that could distinguish civilized America from the unsettled wild. The West was always open for business. The hard part was getting there. The country needed roads and bridges to gap the great divides; or the infrastructure to get from one place to another. Today, like in the past, we bickered about what is infrastructure and how to pay for it.

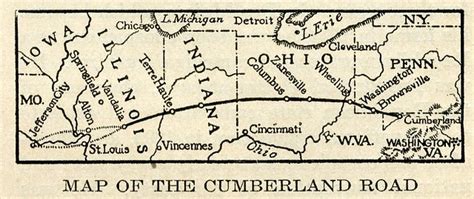

Unlike the British who, without infrastructure, foolishly tried to curb colonial western expansion beyond the Appalachian Mountains. However, our new federal government encouraged western migration, much to the chagrin of native Americans inhabiting the area. In 1811 the federal government began constructing the National Road. The 600 mile road started in Cumberland, Maryland and ended in Vandalia, Illinois. It was America’s first highway west.

Since then the country has built canals, a transcontinental railroad system, as well as a coast-to-coast interstate highway system, and an information highway along with a federally administered air traffic control system. We can also add intercity subway and transit and electric grids, much of it with government funding and assistance.

When Donald Trump was elected president there was a lot of talk about upgrading and improving our nation’s deteriorating infrastructure. The Trump Administration was more concerned about holding back surging groups of immigrants and building “the Wall” along the Southern Border. The one thing Trump realized, as all politicians dealing with infrastructure, is that roads, bridges and walls cost money–tax money. Hence, trying to get Mexico to pay for building the wall sounded like a good idea. But, for all the talk it failed to bring in any pesos. Instead, he pulled money from other government projects. Infrastructure got shoved to the side.

Now that Joe Biden is president, infrastructure has popped back up again. As with Trump’s Wall, the debate centers around who will pay for improving America’s aging infrastructure, with a slight twist on what really is infrastructure in the modern world we live in. And herein lies a problem of perception as to what is a public good.

Generally speaking a public good promotes the general welfare of the country and is free to use–so to speak. For instance, the Interstate Highway system is free for anyone to use unlike a toll road. But we all know that nothing is free. We all put in a our few cents worth with every gallon of gas we buy. The government, however, does not see a return for investors. What gets skewed a bit with a public goods is when we perceive them as a private good for profit. Private companies do not operate and maintain interstate highway systems because there is not profit in doing so. Hence, a public good for everybody; and a cost borne by the public. However, there is a belief in this country that we privatize anything. Just look at the prison system and the space program.

The country in the past has always wrestled with who is gonna pay for such projects. It is sort of hot potato game of passing the buck. Our history is laced with tax avoidance starting with the Boston Tea Party. As the country turned the corner of the 1700s and into the 1800s there was a real need for what was called “internal improvements.” As the country continued to expand getting people and goods from over the mountains and down rivers became not only a political problem but geographical and financial one, too. Thus, internal improvements could be a contentious issue . Projects like Improving ports, building roads and canals and eventually railroads were needed to keep the nation’s commerce growing and expanding. The government always stepped in to help out whether in the form of protective tariffs, land grants to railroad companies or tax breaks for manufacturers.

The financial dilemma, like today, is where to get the money. Between 1790 and 1820 tariffs accounted for ninety percent of the country’s revenue. That has sort of flipped today. According to the St Louis Federal Reserve Bank: “Half of U.S. government revenue in 2019, about $1.7 trillion, came from the public via individual income taxes, of which a significant amount came from payroll taxes, which are paid by employees.”

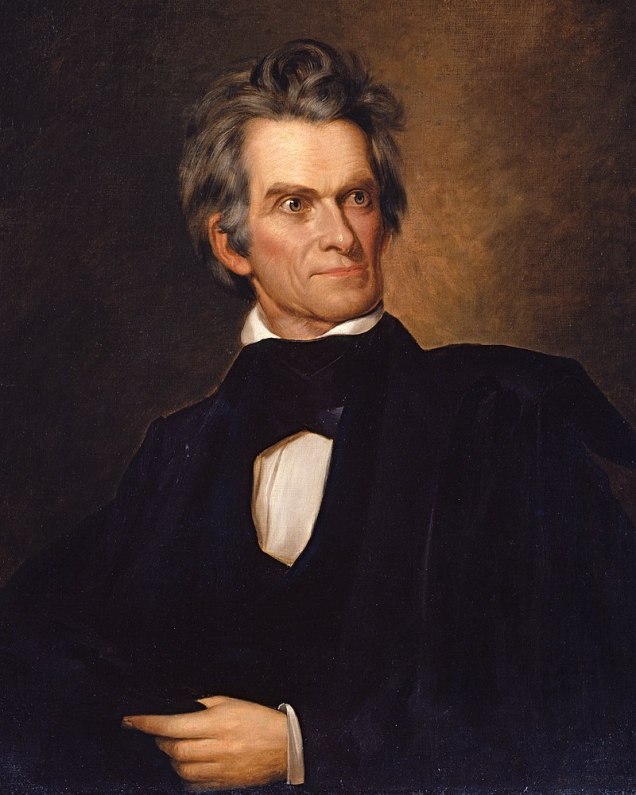

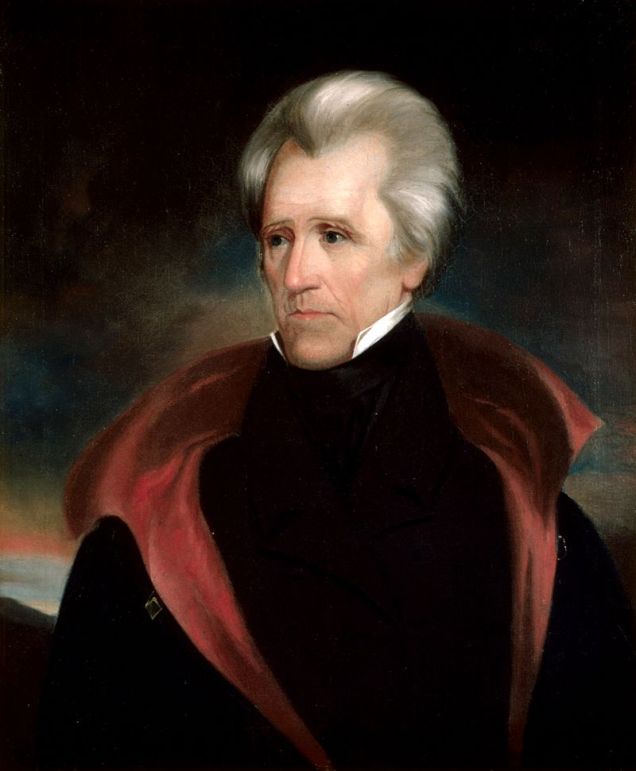

Tariffs have always been a big deal, as evidenced by Trump’s recent trade war with China; and they were a big deal in the 1820s. Now, I am not economist so trying to explain the intricacies of tariffs and taxes. That is not my intent. The tariff of 1828 created some serious political problems and was called, particularly in the South, “The Tariff of Abominations” because it placed high tariffs on imported goods the South depended on. South Carolina, under John C. Calhoun’s direction tried unsuccessfully to get the state to nullify the tariff causing a huge Constitutional and political spat with President Andrew Jackson.

The complication developed with the North’s expanding commercial base and the South’s agriculture base of cotton and tobacco. The North preferred the higher tariff because it provided some protection for its nascent manufacturing industry that was trying to compete with Britain. It could be argued that an expanding internal improvement plan would help deliver manufactured goods to an expanding country. The South, on the other hand, depend more on slave labor and exporting cotton, took a bigger hit importing the now more expensive British goods. Because the South’s economy was not as diverse as the North’s, Southerners felt they took a bigger hit with a higher tariff. It could be argued that politically and economically that the North would benefit more from “internal improvements” while the South paid a higher cost for those improvements through higher tariffs.

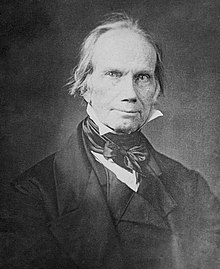

So grappling with internal improvements or what we would call today as infrastructure is nothing new. In May of 1830 President Andrew Jackson vetoed federal funding in the Maysville Road project in Kentucky. This was a pet project of Henry Clay and a project that he felt fit in with his proposed American System. A big part of that plan was a high protective tariff, renewing the charter of the Bank of the United States and internal improvements. Jackson saw it differently. Jackson was not against internal improvements. He was just had no love for Clay. He justified his veto by saying that because the Maysville Road ran exclusively within the borders of Kentucky that it was not an internal improvement that benefited the nation. Since the road was in Kentucky, Kentucky can pay for it. Despite the possibility of the road hooking up with other federally funded roads and canals outside of the state.

Adding fuel to the debate were the normal political and constitutional questions about going beyond the enumerated powers of Congress. But in many ways we crossed that enumerated bridge when Alexander Hamilton created the Bank of the United States and Thomas Jefferson bought the Louisiana Territory from France. Both used Congressional powers not specifically spelled out in the Constitution.

wikimedia commons

Julian Vannerson

or Montgomery P. Simons

From a political standpoint it goes deeper and personal. It is easy to see why Jackson vetoed the Maysville Road bill. Clay and Jackson, despite being from the same section of the country, Kentucky and Tennessee, did not agree on too many issues of the day. Clay had split with the Jacksonian Democrat-Republicans and became a National Republican, later a Whig. Clay had created the American System and like any proposed government plan it came under fire from those opposed to higher tariffs and renewing the Bank of the United States. Jackson hated the Bank with a passion.

However, a lot of Jackson’s animosity for Clay comes from what Jackson supporters called the “Corrupt Bargain.” The 1824 Presidential Election was a contentious election that was thrown into the House of Representatives. Henry Clay was one of the presidential candidates in the race; but also the Speaker of the House. Jackson, despite winning the popular vote and having a plurality–not a majority–of the Electoral Votes, lost the election when the House, under Clay’s leadership elected John Quincy Adams as President. This was a political burn Jackson never extinguished. And dealt out plenty of political pay back to those responsible for his 1824 defeat. (Some of this sounds familiar, today.)

Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl

Today’s infrastructure needs go beyond roads and bridges but the political arguments seem to mark time. Biden is presenting Congress with what could be called a modern “American System.” According to the White House, “This is the moment to reimagine and rebuild a new economy. The American Jobs Plan is an investment in America that will create millions of good jobs, rebuild our country’s infrastructure, and position the United States to out-compete China…The American Jobs Plan will invest in America in a way we have not invested since we built the interstate highways and won the Space Race.”

Biden’s plan is coming under fire on how to fund his ambitious project and defining what is infrastructure. Biden is aiming at busting the britches of those with seven-figure incomes to fund his trillion dollar plus proposed infrastructure program. This has GOPers howling. Not only is the size of Biden’s proposal beyond their budget comprehension (unless you include fighting an unfunded war in the Mideast) and the tax increases needed to fund it. Some of the proposed projects to them are incomprehensible. And that is understandable. The plan calls for creating “good-quality jobs that pay prevailing wages in safe and healthy workplaces while ensuring workers have a free and fair choice to organize, join union and bargain collectively with their employers.” Build next generation industries in distressed communities Redress historic inequities and build the future of transportation infrastructure. To a lot GOPers this sounds like the anarchists and socialists demands of the early 1900s or a Stalinist Five Year Plan. And maybe it is.

The Frontier may have been closed now for more than 100 years. We no longer have people walking beside a wagon following behind a team of oxen for three to six month on the Oregon Trail. We have moved onto an internet information highway. The infrastructure of our country is what holds holds the nation together whether if is made of concrete and steel or digital information moving through cyber space. These upgrades go beyond upgrading an app. But it all seems to boil down to what Congress politically deems is a fundable “internal improvement.”